What Traditional Animation History Can Teach Us About UI Design

It’s no secret that there are good and bad ways of animating. You can either imbue meaning into a transition, or completely, utterly disorient someone. Google’s page on meaningful transitions is perhaps one of the clearest explanations of this principle as it relates to interfaces.

© 2014 Google

© 2014 Google

Animation’s role in web and UI has taken more of the spotlight in recent years. From the rise in CSS and canvas-based animations on the web to Google’s new animation-centric design philosophy, we’re starting to showcase the idea that can actually improve an interface design by showing how elements on a screen move from one state to the next.

Assuming that more and more of our screens will be animated, and that transitions will play a bigger part in our experience with screens, what are some principles we can take from animation history and usher into our modern world of user interface design? The art of animation has a rich, 100+ year history to pull from, and it would be remiss to not carry at least some of it into today.

The First Films

Animation followed on the coattails of film in the final years of the 19th century. Silent film graduated from being a mere carnival amusement into what would become a cash cow industry in a decade. Animation, however, suffered a much longer experimental phase in culture even though the oldest surviving example of animation dates back to 1899—a time before Americans had even seen a movie at their local Nickelodeon.

But of all the examples we could pick from the dawn of animation, we’ll just pick from two that have impact on design: J. Stuart Blackton’s Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906) and Winsor McCay’s Gertie the Dinosaur (1914).

You only have one chalkboard

This wasn’t the first animated effort by the father of animation, J. Stuart Blackton, but this is a milestone in animation history nonetheless. Imagine seeing this a hundred years ago—it must have felt like a dream, watching drawings move and animate before one’s very eyes! By now, people had seen, but were still adjusting to, this new spectacle called film that allowed them to re-watch a part of history. Seeing artwork move, then, might have been even more of a spectacle in 1906.

It’s no surprise that Blackton got this spark of creativity from drawing on a chalkboard—it’s quite a malleable, erasable, forgiving surface. And remember that Blackton was more or less on his own, figuring all these concepts out for the first time. Imagine making drawings ad-nauseum, thousands and thousands of times over, with only minute differences in between them. I’m sure in his experiments, drawings that were wildly different from each other resulted in a jarring, confusing experience to watch. And I can imagine his excitement and dismay upon learning how closely each frame needed to be to its neighbor in order to be perceived as motion. Which brings us to:

Principle 1: Animation must be fluid

Animation between two things must be fluid in order to be perceived as motion.

Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906)

Ok, ok—a landmark in fluid motion it’s not, but you can still perceive the film as a character in motion (barely) rather than an unrelated series of drawings. So in that right, it serves as a low-end benchmark for what the brain does and doesn’t perceive as motion (the film was animated in 20FPS, by the way). If you don’t perceive that as fluid motion, then let that be an example to you what 20FPS looks like!

In addition to that, I’m sure he had a second epiphany while working on this project, possibly much earlier: he only had one chalkboard to draw on. When he draws a cigar on a face, he has to erase part of the face. When the cigar blows smoke over the woman, that part of the drawing must be sacrificed. The question, then, is how do you obscure things while still keeping everything in view?

Notice that in the film whenever something is obscured one time, it’s obscured forever (except for the cut-out parts with the clown). When the cigar appears and obscures the face, it doesn’t go away. When the woman’s face changes, it never changes back. I’m talking, of course, about the destructive nature of chalk, but the principle is that whenever a new thing is shown, an old thing must be covered up. Because, to a viewer, something that’s obscured may as well be gone forever.

How do you obscure something while still keeping it in view?

How Blackton got away with this is obscuring in small, incremental steps. In UI, you can easily reverse showing / obscuring, but even with the ability to “rewind,” the association between two states is lost entirely if there’s no incremental explanation of where something came from and how it got there.

Principle 2: Animation tells a story

Whenever A replaces B, animation must show the history of A becoming B.

Remember: you only get one chalkboard. You can either fill it with drawings that have no relation to one another, or you can tell a story with fluid motion. Animation shows how your initial state gets morphed into something else, and is a form of explanation that requires no words. If done properly, it can be a huge tool for explaining how every thing on a screen got to be where it is. This is true for every state in a design.

The Wonder of Interaction

When was the last time you’ve played with a baby or a small child? Have you noticed how simple it is (mood permitting) to get them to smile? Even the smallest interaction from you will cause their face to light up: there’s a delight in seeing they’re interacting with a real, live, other person.

That never really goes away; even though we take certain digital interactions for granted we still glean pleasure from act of play and from new experiences. We all still find that sense of play in one thing or another, and at the core of play is interaction.

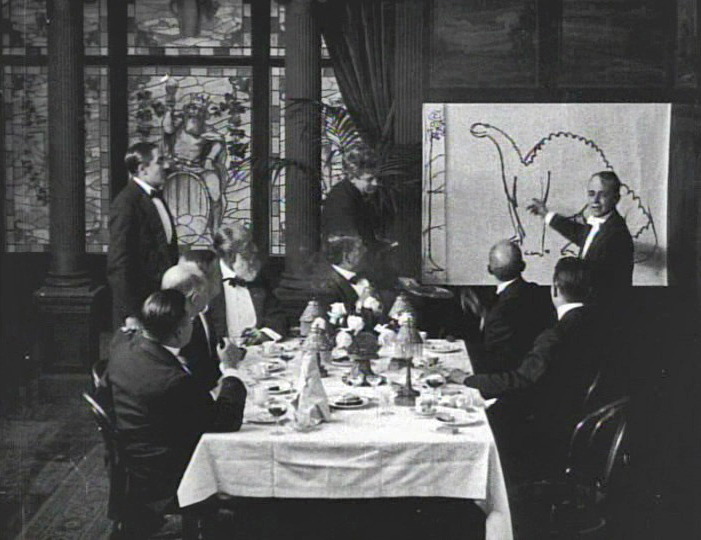

Winsor McCay’s Gertie the Dinosuar (1914) is nothing short of masterful. Many claim it to be the first significant animated work in history, and it still holds its appeal a hundred years later. The more you think about how long the film is, and how many drawings went in to make this (yes, every frame—background and all—is a separate drawing; he did actually draw everything on each frame from scratch every time), it’s staggering to consider the amount of thought that went into the process alone. Add to that the magic way the drawing interacts with the audience, and you have something golden.

The film actually came from McCay’s Vaudeville act, where he would show the film in front of an audience and presumably interact with both the audience and, seemingly, the film itself. There is still a disconnect between the viewer and reality: the viewer is not fooled into thinking this is an alternate reality. But that is not the goal. Rather, this film demonstrates that a viewer can interact with another world they could never be a part of. And, in addition to the childlike sense of wonder it evokes, gives empowerment to the audience to believe that they, too, can interact with something altogether new.

This is only possible through the act of motion: we can connect the dots of our interactions only if we witness the result from start to finish. When McCay tells Gertie to raise her foot and we see her rise up in response, we get that feeling of breaking through the barrier between our world and hers. We watched it happen! Conversely, if it were just a still frame showing a dinosaur with a raised leg, we get the sense that the dinosaur was always doing that, and we had no part in it. It feels much like coming home to a broken pot on the floor. Did I slam the door too hard walking out, or did the dog jump up on the shelf? Or rather yet—was it an earthquake while I was gone? Or did a screw slip a little bit on the shelf? Forgive this crude example, but this point was raised to illustrate a scenario in which we are aware an event occurred, but are confused about our role in the happening of said event. We feel less of an active participant and more of a passive observer.

Principle 3: Animation proves interaction

Animation shows us the difference between what we actively engaging with, and what we are passively observing.

McCay’s subsequent work in animation would go on to inspire other studios to expand on this exciting new storytelling device, most notable of which was possibly Disney. There are so many things now possible with the advent of animation that would be impossible, or, at best, hokey to the medium of live-action film. Drawing and painting have been a part of the human experience for all of recorded history; 2D art has always been a means through which to express things loftier than reality itself—visions of heaven and worlds beyond. It’s no wonder, then, that animation in the following years would coalesce into a rich collection of fantasy and supernatural stories.

Animation [within UI] makes us feel like more of an active participant, and less of a passive observer

Let’s back up for a second before we get too ahead of ourselves: yes, animation, like art, can express the everyday occurrences and can reflect things that are true-to-life. And let’s not pretend, either, that the genres of fantasy and science fiction never existed in live-action. But there is a fundamental split between live-action and animation. Live-action derived from photography, from objective documentation, from depicting reality; whereas animation derived from art, some of it realistic rendering and some of it abstract and/or artistically expressive. So given its nature, animation trends toward expressive over the realistic.

But where am I going with all this? Weren’t we talking about design? Or dinosaurs? I forget. I don’t mean to wax poetic on the narrative properties of animation; only to remind us that, most importantly of all things we can learn from traditional animation, is that animation inspires us to be human. Was all that buildup for—that? That fluff? It may sound cliché, but it’s true. Animation is a purely human-made craft, created to show us human-inspired stories both from reality and the imagination. Who among us weren’t inspired by at least one animated children’s movie? It wasn’t the artwork that inspired us, although there are films that exist that can be called “high art” by anyone’s standards. No, it wasn’t the artwork so much as the excitement of getting to see supernatural (non-realistic) characters coming to life. The magic of animation is imbuing life into something lifeless.

Principle 4: Animation breathes life

Animation can bring lifeless objects to life if the motions mimic life itself.

Gertie the Dinosaur, 1914

Now, that shouldn’t ever be interpreted as everything must move. No, how horrible that would be if everything was constantly moving! But as McCay reminds us—as well as all of the history of animation—we get a sense of wonder and magic from something moving about that we don’t find in still images.

One last point, and then I’m done: I don’t want to confuse animation with live-action here, since live-action has just as much story power as animation does. But remember: with animation, things can move that otherwise could not in live-action. And—just as we live oftentimes with one foot in reality and one foot in our own imaginations, we have access to a new level of communication when we aren’t bound by physics and realistic constraints. And what that means for design—which leans more toward imagination than realism—is that life and inspiration can be breathed into dead, dusty designs simply through life-inspired animations.

TL;DR

- Animation must be fluid in order to be interpreted as movement

- Animation tells a story, and must connect the dots between A becoming B.

- Animation proves interaction by showing us how we interact with another (digital) world

- Animation breathes life into lifeless objects by mimicking life itself.